In the last blog post, we’ve learned a few concrete tools to distinguish between fact and narrative. Now it’s time to apply these tools to seek out patterns of the narratives we tell ourselves about ourselves in response to traumatic events. In order to reveal patterns, we need a structure called seed narratives to help us categorize each narrative into one of the three fundamental forms of narrative that we consistently tell ourselves without realization.

The 3 seed narratives are

1. I am bad

This seed narrative could come in the form of “I am flawed in some way” , “there is something wrong with me”, “I am not qualified”, “I am worse than someone”, “I am a faker”, etc. Generally, one devalues him/herself by stating in some way that “I am bad” when something does not work in one’s favor.

2. I am alone

This is an isolating narrative that one would like to believe that he or she is disconnected from a group/society. A few examples would be “No one understands me” , “I don’t belong here” , “No one cares about me” , “I am special”, etc.

3. I am in danger/not safe

This category generally includes “I don’t have enough time/money” , “People are out here to get me” , “I can’t trust anyone” , “My environment is toxic”, etc. By complaining about external factors, one starts to believe that the surrounding environment is the cause of all the negative emotional reactions that one has.

In general, seed narratives are the summaries of negative narratives. They could feel impersonal to us because they are not specific to our experience. Thus, we need to learn how to trace our own narratives all the way back to one of the seed narratives so that we can notice patterns.

A few questions that we ask ourselves to trace narratives back to a seed narrative:

1. What was I making this mean about myself?

2. What am I making this mean about the others/ the world?

Then with the answer, return to the first question.

Examples:

“Dude, I always spill my water on my pants, why am I so stupid?”

In this example, I am clearly telling a narrative about myself so it’s a better idea to ask the first question: What was I making this mean about myself? The answer here could be “I am stupid” or “I am reckless/clumsy” to be more specific. This fits in the category of “I am bad”.

“My girlfriend slapped me in my face again. I’ve apologized a thousand times even though I’ve done nothing wrong, I don’t understand why girls get so emotional so easily.”

This could be a tricky one. I am mainly complaining about another person here, so it’s better to ask the second question first: What am I making this mean about the others/the world? Examples of the answers could be “All girls are emotional” or “My girlfriend is irrational”. Now with the answer, go back to the first question. Then, we could have answers like “I don’t understand girls”, “My relationship is toxic” or “I’ve done nothing wrong, but no one cares about my feeling”. Based on the imaginary answers, we can categorize them into either “I am alone” or “I am not safe”. It can also be both depending on individual cases. It is completely normal to have a narrative that falls into one or more categories of the seed narratives.

Before we go into some practice, we’d like to introduce one more key point: Manifestation

Manifestation is the particular form in which you are telling yourself these narratives consistently over time. In other words, it is the last layer before the seed narrative when you trace your narrative back to a seed. It is going to take the form of a childlike phrase. For example, the manifestation of “She doesn’t like me” could be “I am annoying” which uses a simple phrase “annoying” to describe how I feel about myself. A manifestation usually doesn’t take the form of anything too complicated such as “I have social disorders”, but a simple phrase that feels like a dagger stabbed right into your heart when you say it to yourself. If this doesn’t make sense yet, don’t worry. We will come back to it with better examples when we are dealing with later steps of the narrative excavation practice.

As a warm up exercise, we would like you to come up with your own imaginary story like the one from the last blog. It doesn’t have to be long, but allow yourself to flow through the story without analyzing it first. Once you have the story, create a fact vs. narrative table using the tools: narrative indicators, implicit narratives and core emotions.

You’ve done it? Great job.

Next, let’s pick a casual event that’s happened to you recently. It could be as simple as having dinner with your friends and family. Try to picture yourself back in the scenario again, and write down the story so that you can make a fact vs. narrative table again.

Practice makes perfect.

Time to move on to the real deal. Remember, we only pay attention to the narratives in response to traumatic events in a narrative excavation practice. The 5 core emotions (fright, fear, anger, sadness and pain) are the key here to help us identify a traumatic event. Now, we’d like you to pick a traumatic event in which you experienced one of the core emotions. On a 10 scale of emotional intensity, find one that is at about 2-3. In other words, the event is somewhat traumatic but not strong enough to haunt you for the rest of your life. Again, write it down and create a fact vs. narrative table. In addition, trace each of the narratives on the right hand side of the table back to a seed narrative and write them down in a separate column.

Before we move on, there’s something important to note. From this point on, the process of excavation will become more and more confrontational. You do not have to feel obligated to follow all the instructions, but also know that the more vulnerable you are willing to get, the more insights you will gain from it.

If you chose to keep going, we would like you to now pick a traumatic event in which you felt 5-7 on a 10 scale of emotional intensity. Repeat the same process as the last one. Find the fact and narrative, then trace those narratives back to a seed.

As our story becomes more and more personal, start to pay closer attention to the 5 core emotions. The emotions that we felt during the events are fact rather than narrative. For example, “When John was going on and on about politics, I felt like he was being annoying.” If I felt anger in this case, I would put “I felt anger” on the left hand side of the table as a fact. Then on the right side, I would write “John was being annoying” as a narrative. When we encounter a feeling language that is not in the form of core emotions, simply ask ourselves which word in the 5 core emotions would best characterize our feeling at the time. Also worth noting, it’s possible to feel multiple emotions simultaneously in varying degrees.

If you’ve followed thus far, great work! Your dedication towards this practice will show results over time just like how a handbalancer spends years of training to achieve great results.

Finally, it’s time to face the devil. Write about an event that you consider to be the most traumatic/pivotal. Take a second to imagine yourself being there at the moment. Lay down all the details from it. Follow the same process as before.

If you did follow each and every step here, you should now have 3 tables in total from your personal traumatic events at this point. This next step is called meta-analysis. With the tables you created, line them up vertically. Go through the narratives and circle all the decisions you made about yourself. Look for patterns and repetitions of the seed narratives. At the end, write a reflection, new insights, and realization from this process.

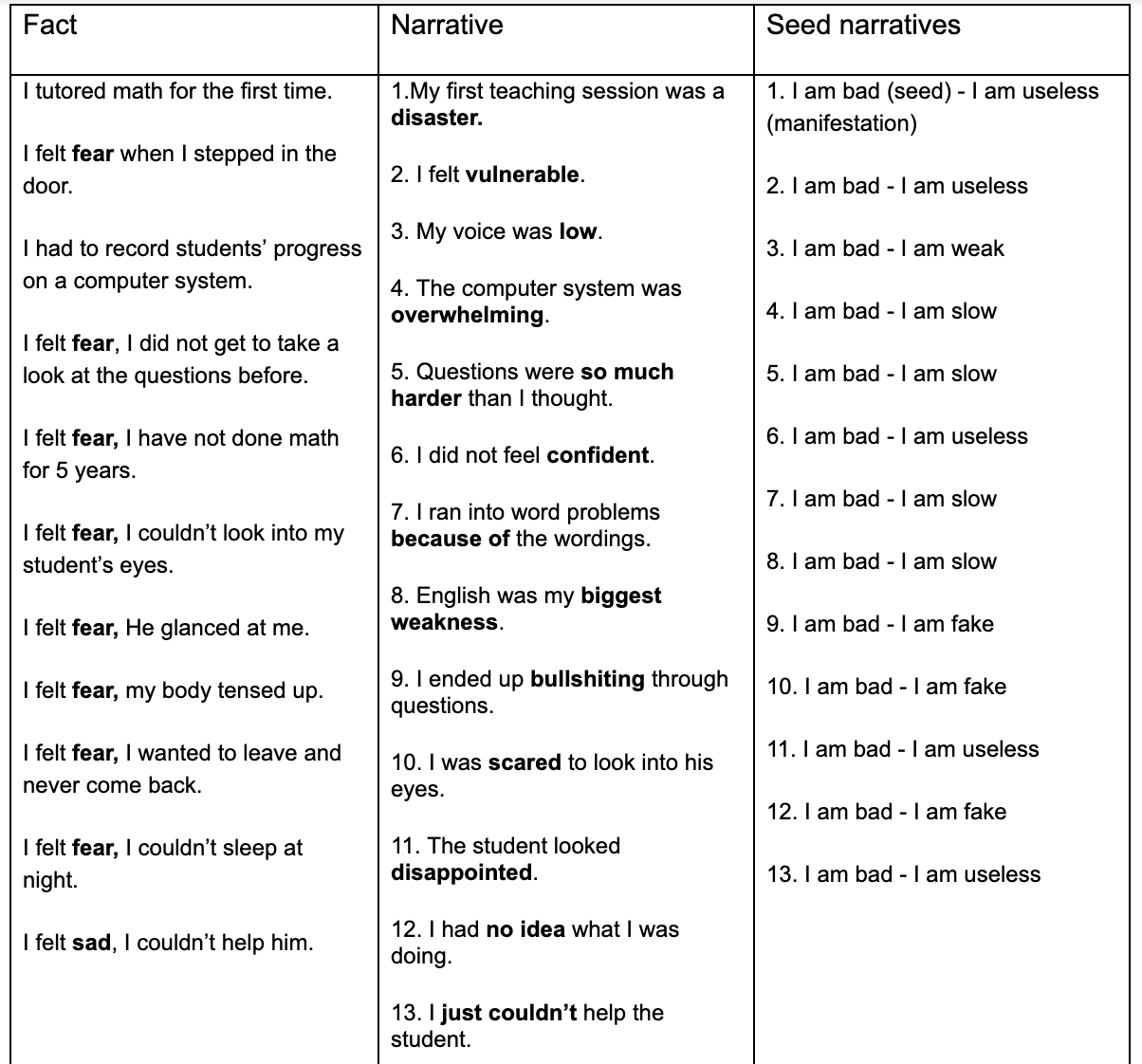

As an example of all the steps, we are going to use one of Bruce’s (myself) personal stories from his narrative excavation practice. Since this was personal to Bruce, details might not apply to everyone, but we can use it as a guideline to help us understand what we are trying to achieve here.

This is a traumatic event in which Bruce experienced multiple core emotions at level 5-7:

“The first time I tutored for SAT math was a disaster. I felt vulnerable when I stepped in the door. My voice was low like a mouse. The computer system I had to use to record students’ progress was overwhelming. The questions on the textbook were so much harder than I thought originally and I haven’t had any chance to take a look at them before. On top of that, I hadn’t done SAT math for 5 years, so I did not feel confident teaching it at all. I ran into a few word problems that confused me big time because of the wordings in English. Oh god, I felt like English was my biggest weakness at the moment. I ended up bullshitting through many questions. I was too scared to look into my student’s eyes, and I knew he looked disappointed. He glanced at me from time to time as if he knew I had no idea what I was doing. He’s spent all these money trying to get help, but I just couldn’t do the job. My body kept tensing up, and I wanted to get out as soon as possible and never come back again. It was a sleepless night for me.”

To clarify how to get from narrative to a seed narrative and its manifestation, let’s use example #1:

1. My first teaching session was a disaster.

Questions: What was I making this mean about myself?

Answer: I am not qualified to teach.

We ask the question again,

Answer: I am useless. (Manifestation)

Ask the question again,

Answer: I am bad. (Seed)

Reflections:

“I tell myself the narrative that “I am bad” a lot. A few particular forms in which I tell myself this narrative are “I am fake”, “I am useless” and “I am slow”. During the excavation process, it does remind me of childhood memories when my parents and teachers called me slow-minded, and it caused some emotional reactions within me. This has been a consistent way of me telling myself that I am bad. Now that it’s revealed to the surface, I can become more aware of this simple phrase. The whole excavation process did take so much of my brain power, trying to put feelings into words. Some thoughts are hidden in the mud, especially when it’s hard to remember the exact feelings after the traumatic events. Even during the events happening, not being aware of the feelings could be a missed opportunity. The longer you wait, the harder it will become to excavate. All in all, it feels tiring to analyze emotions and thoughts that naturally occur to us on a day to day basis, but this is where practice plays a huge role. I do see myself catching narratives right on the spot more frequently as I practice more.”

Going forward, Bruce’s example will be used again to help us understand the next step on how to deal with narratives once you have revealed their forms and patterns.

In the next blog, we are going to look at the consequences/side effects of the narrative once we believe them to be true. We will also learn to identify payoffs/motives.

The Narrative Excavation practice comes from Devin Kelley, feel free to follow him on Instagram at @devinpkelley if you are interested in more.